Composition

To me, music composition, in its truest and broadest sense, is not a specialised, separate, isolated endeavor, nor a discipline to be cordoned off within the hierarchy of specialised musical labor. Rather, it is a fundamental mode of being within Music itself, a generative act that arises naturally from the matrix of musical thought and practice. To compose is not merely to write, nor simply to invent: it is to think musically. It is to participate in the ongoing process of making and shaping musical tones (notes in the score) in ways that reflect both individual voice and universal order.

This understanding of composition challenges the prevailing model that sees it as an autonomous, innovation-driven enterprise, detached from performance and improvisation, and embedded in the narratives of progress, stylistic rupture, or aesthetic rupture. My personal philosophy of music composition, or more precisely, score composition (since performance itself is also a form of composition, albeit in a different medium), rejects both the fragmentation that severs music from its cultural, sensory, and cognitive origins, and the fetishization of novelty that elevates formal experimentation above expressive or ontological meaning.

Notation is not tone. It never was. Nor is it a perfect translation of musical thought. Notation is an interface, a porous, contingent, flexible domain where visual symbol and aural presence intersect. It exists not to fix music, but to suggest its contours. In this view, notation is not univocal or rigid, but a gesture, a means of inviting performance, of opening the door to interpretation and transformation. It lives, therefore, at the threshold between the oral and the written, where memory, imagination, and real-time decision making converge.

The Western tradition has long emphasized the written as the seat of authority in music. But following thinkers like Walter Ong, we must acknowledge that oral and literate musical cultures coexist and interact in ways far more complex than linear narratives of "progress" allow. Composition, then, becomes a dynamic interplay: between the written and the improvised, the premeditated and the emergent, the score and the moment, the symbol and the breath.

In my classroom, this idea is not theoretical, it is lived. That is, with my students, I move between oral improvisation (such as contrapunto alla mente, a cappella discants over drones, or extemporaneous keyboard partimenti) and written counterpoint (Fuxian species, canon, fugue), always weaving a thread between res facta and res ficta. The written and the improvised are not adversaries, but collaborators. Notation is not a prison, but a poetic trace, somethingl that reanimates in contact with living sound.

Stylistic categories, while historically and culturally meaningful, are, to me, ultimately insufficient containers for the depth of musical expression. That is, I do not approach style as a museum taxonomy or a historically materialist science, but as a surface manifestation of something far deeper: the perennial and cross-cultural foundations of musical meaning. In this light, composition is not primarily the organization of style, but the revelation of what lies beneath style, what Plato named the five Magista Genae (the give Great Ideas or Genres): the same, the different, stasis (repose), kinesis (motion/change), and being.

These universals manifest as repetition (the same), imitation, variation, and transformation (the different), cadence and repose (stasis), modulation, transition, and dynamism (kinesis), and the ontological presence of musical tone itself (being). A composer does not invent these; they are always already there. Rather, the task is to listen deeply, to synthesize inherited forms and structures in ways that speak to the eternal drama of musical tones: a drama that transcends historical period or cultural affiliation.

Against this backdrop, one can speak of the prevailing logic of fragmentation in much contemporary art and art music. It is often claimed today that the artist must not only reflect the brokenness of our time but even accelerate it, that by portraying things even more disintegrated than they are, the artist proves his historical authenticity. But such logic is self-defeating. It is akin to someone who joins a tyrannical regime not to resist it, but to document that they lived through it. Surely, one may also inhabit a time in opposition to it.

It is said today too that the modern artist - or musician/composer - must reflect the "compartmentalized consciousness" of today, a splintered view of reality in which objects no longer appear as wholes, but in formal chaos. But such art, which revels in dismemberment, does not tell the truth about the world. It merely mirrors confusion. And mere reflection is not the work of art. The task of the composer (of any artist) is not to reproduce entropy, but to reorder, to restore, or at the very least, to mourn the temporary loss of order with dignity. A work that does not offer wholeness must at least offer the grief of its absence. To do otherwise is to triumph in the spectacle of destruction.

There is something healing in a composition where wholeness has been restored, or even gently evoked in its absence. In a fragmented world, the work of art can either collapse into the general disintegration, or it can serve as the site of return. As in certain styles of ancient Chinese painting, where a single blossom evokes the full invisible tree, so too should a musical phrase contain within it the reverence of the whole it implies. Fragmentation that refers to nothing, that exults in its own autonomy, becomes superficial magic: a kind of sterile simulation, floating above time and space like a false icon, gleaming with a light not of truth but of oblivion.

It is not enough to say that fragmentation is a beginning, a step toward something yet to come. It has revealed itself too clearly. We must not confuse the uniformity of destruction with the unity of essence. One comes from fullness, the other from scarcity. Art that simply joins the vortex of dissolution loses its sovereignty, becoming not a product of the human but of the machine of fragmentation itself. Press a button, and out comes another composition, another abstraction, another annihilation.

This is not Orpheus. Orpheus did not conquer the underworld by becoming darker than it. He sang: a song luminous enough to draw Eurydice out of the shadows.

In my opinion, if there is a material repository of musical universals, it is folk music: that vast, interwoven inheritance of sung tradition, often anonymous, often unwritten, always alive. Like Zoltán Kodály, I see folk song not as primitive material to be elevated by "higher art", but as the purest embodiment of musical truth: modal integrity, organic form, archetypal contour, human cadence.

Memorizing, singing, and improvising on folk melodies forms one of the basis of my compositional pedagogy. This has nothing to do with "vocal technique", but rather with a form of "poetic (or melopoetic) solmization": a recovery of a poetic dance between hands and larynx, where the arm moves through euphonic space, at the same time as the interval is sung and felt vibrantly in the body. Here, diction takes on the ancient meaning attributed by Aristides Quintilianus: not mere pronunciation, but the shaping of tone with intelligible soul.

By singing and inventing over drones, by absorbing the tonal DNA of ancestral tunes, students come to understand music not through abstraction, but through lived resonance. Composition becomes a natural extension of these sonic encounters: not an imposed architecture, but an unfolding.

It was precisely in this spirit that I received my earliest and most enduring compositional - musical - upbringing with Don Salvador Chuliá in Valencia, Spain, a composer, conductor, educator, and my teacher between the ages of 10 and 17. Though my music today bears little stylistic resemblance to his - in superficial appearance - I consider himself my true Music teacher and his humble disciple, and I proudly count myself as a link in the long lineage he inherited and transmitted: from Alessandro Scarlatti (student of Pasquini and Carissimi), Gaetano Greco (student of Salvatore and Ursino), through Francesco Durante, Giovanni Paisiello, Nicola Vaccai, Emilio Arrieta, Felipe Pedrell, Bartolomé Pérez Casas, Modesto Rebollo, Ernesto Pastor Soler, and finally, Salvador Chuliá himself.

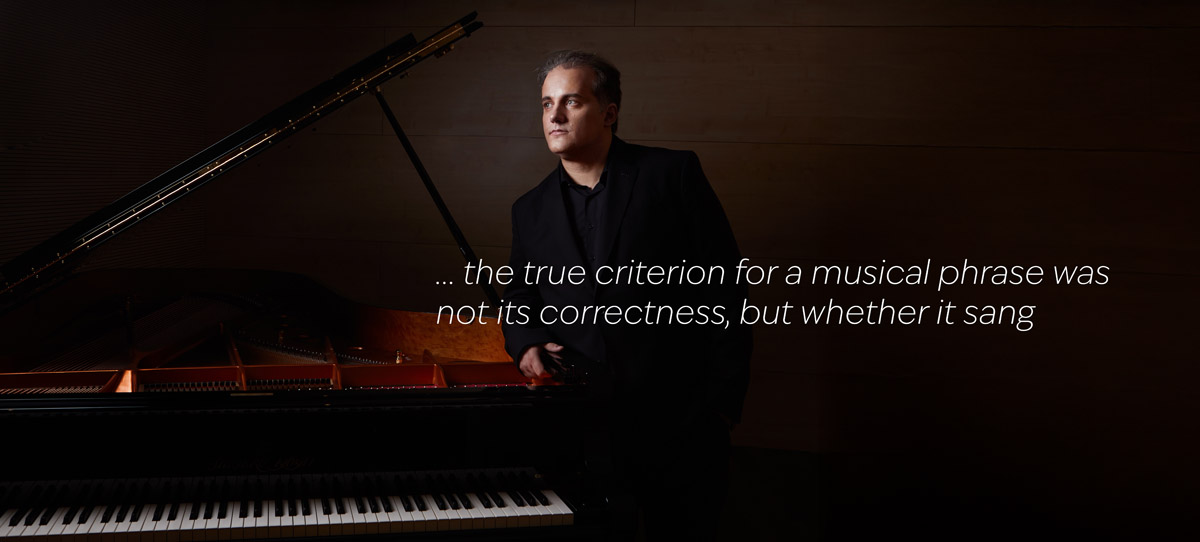

From Don Salvador I learned that composition was not a set of abstract principles, but the living logic of song ("el canto", "el melos") and that the true criterion for a musical phrase was not its correctness, but whether it sang. "No hay fallos, Josu, pero no canta", he used to tell me, about my counterpoint exercises. "There are no mistakes, but it doesn't sing", he said, and those words became the bedrock of my musical thinking. He taught me, without ever naming it as such, that conatus, the scholastic idea of continuous motion and inner inclination, is the essence of both music and life: that everything falls, as in a cadence, but everything must also resume, as in the sea wave that crashes only to rise again. From him, I learned that to compose is to restore movement, not to petrify it; to write the sea, not the rock.

Chuliá transmitted to his students not merely the bricks and mortar of musical technique, but the meaning of musical art and how it connected to life. As a very spiritual person, he likened the relationship between form and emotion in music to the relationship between reason and faith. One of his sayings, similar to that of Nadia Boulanger, describes this beautifully: "One must approach music with serious rigor and, at the same time, with a great, affectionate joy". He sought to bring together intellect and feeling, emotional expression always guided by rational control, and structure always infused with inner light.

To end, I will add that, in terms of traditions, as a score composer, I most likely align with a certain qualified idea of what today people call polystylism - despite my hesitations about the label (or taxonomies in general). In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, so-called polystylism (as championed by composers such as Alfred Schnittke, Luciano Berio, Sofia Gubaidulina, George Rochberg, and John Zorn, but not only) emerged as a way of reconciling the fractured stylistic landscape of modernity. But polystylism must not be confused with eclecticism (a passive collage of materials) but rather understood as a deliberate, coherent fusion of multiple musical identities. It is not the juxtaposition of styles that matters, but the synthesis of their expressive possibilities into a singular compositional voice. In a certain sense, all great composers were poly stylists, as the great Wye Jamison Allanbrook taught us in her masterful book about Mozart, for example.

In this regard, polystylism echoes the musical universals I described above. It acknowledges that style is never pure, that no musical utterance is without lineage or influence, and that the task of the composer is not to mask or erase that complexity, but to integrate it. The result is not pastiche, but plural unity: a form of expression that is at once personal and historically aware, resonant and synthetic. But history seen here not as a science, but as circular momentum .

As my admired George Rochberg once noted, a new artistic music (should it come into being) would require at least three principles:

1. Parallel/serial functions: coherent melodic continuities that unfold across multiple layers

2. Memory functions: self-perpetuating structures of repetition and variation that generate coherence and recognizability

3. Logical directionality: goal-oriented relationships that mirror the teleological behavior of the central nervous system

These ideas, far from excluding folk material, improvisation, or oral traditions, suggest that the most future-facing music will also be the most integrative: the music that welcomes memory, intention, motion, identity, and contradiction into its very form, leaving behind the a-semantic abstraction of a lot of academic music of the 20th century, with its solipsistic, an-anthropic fetishisation of sound over tone.

But ultimately, for me, composition is not a prescriptive act. It is not the imposition of a system, nor the codification of an ideology. It is an invitation: to performer, to listener, to co-create meaning. It is not the solitary heroism of the creator, but the quiet dialogical process of listening, shaping, and offering. In this light, the composer is not a master of materials, but a participant in a wider ecology of sound: a servant of musical tone, of gesture, of breath.

So, to me, composing means to mediate between past and present, between idea and presence, between silence and form. It is to reveal, not to dictate. To call forth, not to impose. It is to stand at the meeting place of memory and imagination, and to make something that feels (however briefly) inevitable.

And if I am able to stand there today, between those spaces, shaping those lines, it is because once, a long time ago, Don Salvador Chuliá showed me how. With his voice, his gesture, his love of music, and his fidelity to the invisible sea behind every musical and emotional wave.

Compositions by Josu De Solaun

Chamber

Extravío, para recitador y piano

reciter and piano

Extravío is a piece that lives in the in-between—the space where speech becomes song, and silence carries meaning. It is a melodrama, or melólogo—a form I’ve always found hauntingly intimate, suspended between theatre and music, body and thought. In this work, the piano doesn’t accompany the voice; it converses with it, surrounds it, contradicts it, breathes with it.

I based Extravío on poems by César Simón—one of the most quietly luminous voices in Spanish literature. His poetry moves in small gestures, in moments that might be missed if not carefully attended to: a passing shadow on a wall, the sound of a drawer closing, a leaf trembling in the breeze. It is poetry of lo cotidiano—the daily, the domestic, the peripheral—but through it shines something eternal, mysterious, almost metaphysical.

The title, Extravío (which can mean loss, straying, derailing, or simply being elsewhere), came to me as a way to name that gentle sense of disorientation one feels when staring too long at the familiar. The piece unfolds like a walk through memory, through the folds of ordinary life where time doesn’t quite behave. The reciter speaks, sometimes clearly, sometimes whispering into absence. The piano traces the invisible: an emotion left unsaid, a thought left hanging, the ghost of a childhood afternoon.

This work is not meant to dramatize, but to listen. It is slow, hushed, inward—like reading a diary out loud, but only for oneself. The poetry and music meet not in climax, but in communion. They blur.

In composing Extravío, I wanted to create a ritual of noticing. A fragile meditation on what remains when everything seems to slip away: a voice, a chord, a breath.

Octeto de Cuerdas

four violins, two cello, two violas

This String Octet is an act of reverence—a double homage to two towering monuments of the form, Mendelssohn’s radiant youth and Enescu’s mythic density, but above all to my teacher and spiritual guide in the art of counterpoint, Salvador Chuliá. It is to him, to his quiet rigor and expansive soul, that this work is dedicated. It is a meditation on melos—that sacred thread of music as the interweaving of singing lines, of voices bound in conversation, of thought turned to melody.

From the very first bars, the octet asserts itself not as mass, but as polyphony—eight voices, each distinct yet inextricably woven, unfolding in a dance of tension and release, divergence and convergence. The music is dense but never heavy, clear yet never simplistic. It sings, argues, laments, rejoices—all through line, through direction, through breath. This is music that believes in the power of melody not as decoration, but as architecture. Each note a decision. Each voice, a path.

At its heart lies an apocalyptic fugue—a whirlwind of contrapuntal forces colliding and spiraling toward collapse, where the learned craft of line becomes ecstatic utterance. Here, the fugue is no academic exercise, but an invocation of chaos tamed by form, emotion restrained by discipline, the many moving as one. And then, as if from the wreckage of that storm, rises the final Adagio: slow, spacious, and sublime. A hymn of gratitude. A farewell. A stillness that carries the weight of all that came before it.

This octet is not only a tribute to a teacher, but to the unbroken chain of musical lineage—to the invisible voices that live inside every note we write, every phrase we sing. It is a work of faith: in melody, in memory, and in the luminous geometry of counterpoint as a mirror of the human spirit.

Quinteto de Viento Metal "Valencia"

two trumpets, horn, trombone, tuba

VALENCIA is a musical offering to the land that shaped my ears, my memory, and my sense of rhythm. I wrote this brass quintet as a tribute to the wind band tradition of my childhood—to the music that echoed through the narrow streets during the Fallas, during processions, during fireworks and farewells, joy and mourning alike.

In Valencia, brass instruments are not just instruments—they are voices. They laugh, they shout, they cry, they accompany every rite of passage, every gathering, every silence that needs to be filled with warmth. Growing up, the sound of the band was the sound of life itself: exuberant, raw, communal. It was everywhere—on balconies, in parades, in distant rehearsals carried by the wind.

This piece doesn’t attempt to reproduce those memories literally. Rather, it is my evocation of that spirit: the blend of solemnity and celebration, of elegance and earth, of structure and spontaneity. It is a street festival remembered through the prism of chamber music—a gesture of love, a return, a transformation.

VALENCIA is not only a place. For me, it is a sound. And this quintet is my way of saying: I remember.

Cuarteto de Cuerda Nr. 1 "Tombeau: a Bernardo de Clairveaux"

string quartet

Premiered at the 12th edition of the Málaga Clásica International Chamber Music Festival, this work was commissioned as part of a program titled Resonancias del Espíritu (“Resonances of the Spirit”), reflecting on how music can awaken and transform our inner world. Inspired by Juan Gil-Albert’s poem Tombeau: a Bernardo de Clairveaux, dedicated to the 12th-century Cistercian monk Bernard of Clairvaux, the quartet explores the spiritual and existential tensions between the earthly and the divine. Structured in four movements—Luchas (Struggles), Bosques encantados (Enchanted Forests), Pacto (Pact), and Dudas (Doubts)—the piece unfolds as a metaphysical journey where sound becomes introspection. Its premiere, led by violinist Jesús Reina alongside Øyvind Gimse (cello), Nicolas Dautricourt (violin), and Laura Romero Alba (viola), was praised for its timbral richness, contemplative depth, and the musicians’ deeply engaged performance, leaving a lingering impression of unresolved mystery and spiritual resonance.

Capriccio Concertante

piccolo, flute, two B-flat trumpets, three trombones, euphonium, and solo piano

Scored for the same rare and idiosyncratic instrumentation as Janáček’s Capriccio—piccolo, flute, two B-flat trumpets, three trombones, euphonium, and solo piano—Capriccio Concertante is both a tribute and a reinvention. Composed in homage to one of my most beloved composers, Leoš Janáček, whose emotional volatility and melodic angularity have long haunted my imagination, the piece unfolds in two contrasting movements: Allegro Marziale and Lento Cantabile. The opening movement, resolute and sharp-edged, is built from bold brass utterances and percussive piano gestures, evoking a kind of ceremonial procession fractured by modernist dissonance—a martial dance in unstable terrain. The second movement, by contrast, inhabits a world of suspended lyricism: a Lento Cantabile that sings in melancholic arcs, with the piano weaving introspective filigree through the sonorous brass textures. Dedicated to the Philharmonic “Paul Constantinescu" of Ploiești, the work is also a silent bow to the city’s poetic soul—home to Nichita Stǎnescu, a poet both my wife and I deeply revere. In this sense, Capriccio Concertante becomes a dialogue not only with Janáček, but with Romania itself—its poetry, its breath, its brass.

Trio de Cuerdas "Syzygia"

violin, viola, cello

Syzygia—named after the rare astronomical alignment of three celestial bodies—is a one-movement string trio that unfolds as a tacit homage to Arnold Schoenberg’s formidable String Trio, yet it departs into its own philosophical and sonic orbit. Rather than dwelling in binary oppositions—subject/object, self/other, light/dark—this piece seeks the fertile tension and mysterious equilibrium that emerges when three distinct entities coexist, collide, and converge. In Syzygia, the violin, viola, and cello are not adversaries in dialogue, nor pairs in dialectic, but gravitational presences weaving an unstable unity—a constellation in flux. The music traverses zones of conflict and communion, tracing arcs of dissolution and coalescence, as each instrument both resists and surrenders to the force of the others. It is a meditation on triadic being: the way truth, beauty, and time are rarely singular or dual, but refracted through a third voice—unpredictable, uncanny, illuminating. In this work, the trio becomes not a structure, but a condition of being.

Sonata para violin y piano Nr. 1 "Reina"

violin and piano

Named for Spanish violinist Jesús Reina, Reina is a sonata of sovereignty—not dominion over others, but self-mastery, nobility of spirit, and the regal stillness that precedes speech. Drawing inspiration from Spanish folk idioms—Andalusian sighs, Castilian pulses, Levantine laments—it is a sonata of inner rule, of graceful strength, of a crown worn inwardly.

The violin sings not as supplicant, but as sovereign; it leads and listens, commands and yields. The piano does not accompany but reflects—sometimes like a sword being drawn, other times like an echo in an ancient palace. Themes unfold like ceremonial processions, with sudden moments of flamenco-like freedom breaking the courtly architecture.

Sonata Para Violin y Piano Nr. 3 "Margarita"

violin and piano

A sonata of faded innocence and quiet revelations, Margarita is dedicated to Norwegian violinist Anna Margrethe Nielsen—whose gentleness, radiant inner life, and luminous artistry gave this piece its breath. The title nods to Goethe’s Faust, to the tragic purity of Gretchen, yet this Margarita is not a victim, but a vessel of silent strength, of deep feeling borne without spectacle. It is a sonata of memory and grace, of things that pass and still remain, braided like Margarete’s Spinnrade—the spinning wheel that turns fate into thread, and longing into song.

The music draws upon the soft light of the north, echoing Norwegian folk motifs that drift through its pages like snowflakes on old windows—translucent, trembling, ungraspable. There are echoes of lullabies, of pastoral dances turned inward, of landscapes shaped as much by silence as by sound. And within that quietness: the impression of a loss long carried—Anna’s father, taken too soon, whose absence still hums like a distant ison beneath everything.

The violin never shouts, but it aches. Its lines move with a tenderness that never resolves, always circling a center that cannot be reached. The piano responds not with certainty, but with shade—its harmonies murmuring like prayers spoken too late, its figures like the hesitant steps of someone revisiting a room no longer inhabited.

At the same time, there is in Margarita a quiet joy, a love that pulses through the sorrow: Anna’s devotion to her partner, Jesús Reina, a meeting of two musical souls who share both stage and life. The piece is imbued with that love—with her affection for Spain, for warmth, for sunlit colors even in the midst of Nordic twilight.

Sonata Para Violin y Piano Nr. 2 "Francesca"

violin and piano

Francesca is not a tragedy, but an act of defiance—of survival through fire, of poetry drawn from fracture. Inspired by the elemental intensity of violinist Franziska Pietsch, this sonata is a forged landscape where the mythic Francesca da Rimini, swept by passions beyond herself, merges with a woman who crossed invisible walls with only her sound as shield. The fire in this work is not romantic—it is metaphysical. It is the fire of remembering, of becoming, of never looking back even when silence surrounds you.

From its first bars, Francesca sings in embers and sparks. The violin is searing, mercurial, untamed—its phrases etched with both Slavic melancholy and German rigor, like a voice carved into frost. Czech folk elements flicker beneath the surface, not as quotation, but as residue: a haunted rhythm here, a plaintive interval there, memories half-erased by history and time. The piano is relentless and unpredictable, echoing the architecture of walls—visible and invisible—collapsing inward and outward.

But what animates Francesca most deeply is not its history, but its philosophy: the belief that the artist is not one who speaks, but one who bears witness. This is music that moves through storms with its eyes open, that transforms constraint into clarity, exile into illumination. There is no catharsis, no salvation—only the furious elegance of forward motion, of dancing while the world burns behind you.

Sonata Para Violin y Piano Nr. 4 "Amarilli"

violin and piano

A sonata of metamorphosis, Amarilli is named after the madrigal and dedicated to French violinist Amaury Coeytaux. It channels the spirit of transformation, invention, and theatrical reinvention. Drawing on the folk traditions of the Auvergne—both rustic and radiant—it weaves together old dance forms, spectral fugues, and bursts of ecstatic improvisation.

Here, the violin is a chameleon: part trickster, part mystic, part wanderer. The piano shifts accordingly—from earthbound anchor to celestial mapmaker. The music refuses stability, instead choosing to become—to break and recombine, to question and seduce.

Cuarteto de Cuerda Nr. 2 "Insomnia"

string quartet

Insomnia is not merely the absence of sleep, but the presence of something that refuses to rest—thoughts, memories, ghosts, truths. My String Quartet No. 2 bears this title not as a medical condition, but as a metaphysical state: a condition of hyperconsciousness, of being caught between night and thought, silence and noise, forgetting and remembering.

The music unfolds like the interior of a sleepless mind: pulses that refuse to resolve, fragments of themes that obsessively return like a heartbeat or an anxious breath. The quartet begins in darkness—not a theatrical darkness, but the quiet, cerebral kind, where even the smallest sound becomes immense. The instruments whisper, argue, reflect; they chase motifs that slip through harmonic traps, they echo one another like wandering minds seeking dialogue in a vast, interior void.

This is not a quartet of repose, but of exposure. It is music stripped of consolation, often raw, sometimes tender, always searching. The texture is heterophonic, restless. There are moments where everything seems to unravel—glissandi, sul ponticello tremors, pizzicati like dripping thoughts. And yet, through the agitation, there are oases: fleeting chorales, stillnesses suspended in air, windows that open momentarily onto something numinous.

At its core, Insomnia is a string quartet about being awake—not physically, but existentially. It’s about that terrifying clarity which only comes at 3 a.m., when masks fall, and one’s own mind becomes both refuge and prison. In this way, the quartet becomes an inner monologue fractured into four voices: inner child, inner critic, dreamer, and witness.

The piece does not end with resolution, but with acceptance: the recognition that the night does not promise rest, only depth. And in that depth, something true can emerge—fragile, flickering, and real. Insomnia is a nocturnal rite. A confession made in harmonics. A testament to the soul’s refusal to close its eyes.

Trio con piano "A Thing With Feathers"

violin, cello, piano

“Hope is the thing with feathers / that perches in the soul”

These lines by Emily Dickinson are both epigraph and heartbeat for my piano trio, A Thing with Feathers—a work dedicated to the invisible, persistent presence of hope, especially in times when it feels most impossible. Composed as a gesture of faith amidst fragmentation, this piece is not naïve in its optimism, but resolute: it holds space for beauty in the midst of chaos, for lyricism without illusion, for fragility as a form of strength.

The trio is built around the idea of lightness—not as levity, but as elevation. The violin often takes on the role of a soaring inner voice, birdlike in contour yet deeply human in tone, while the cello grounds the music in a kind of contemplative sorrow. The piano moves between these poles—sometimes delicate as breath, sometimes urgent as prophecy. The ensemble breathes together, as if searching for a shared language that might still be possible.

Motivic cells emerge and re-emerge like questions whispered through closed doors. Melodies are hesitant, tremulous, often shadowed by harmonic ambiguity. And yet, through the ambiguity, there is a constant reaching—upward, outward, toward. The piece does not offer hope as certainty, but as gesture: as something that continues despite everything, that hums even when unheard.

This trio is a work of its time, but also outside of time. It asks how one might still sing when the world is fractured. It asks what it means to believe—not blindly, but poetically, philosophically, spiritually—in the endurance of light. In A Thing with Feathers, hope is not a sentiment, but a form of resistance. A vibration in the chest. A wingbeat in the dark.

Solo

Preludio, Tiento, Diferencias y Fuga para piano solo

Premiered in November 2023 at the Auditorio de Catarroja as part of a concert in homage to my beloved teacher Salvador Chuliá, this four-part work is both a gesture of reverence and a meditation on inheritance. It is not a suite in the conventional sense, but rather a spiritual arc—a pilgrimage through musical forms that have shaped my thinking, filtered through the lens of memory, discipline, and love.

The Preludio opens as invocation—tentative, spacious, almost improvised. It searches not for brilliance but for direction, like the first breath before a thought becomes speech. It clears the air, makes room. The Tiento, drawn from the Iberian keyboard tradition, is introspective and archaic—yet not nostalgic. It winds through modal landscapes and veiled dissonances, evoking the mystical geometry of Renaissance counterpoint while revealing the tremble of the present beneath its surface.

In the Diferencias, variation becomes drama: a dialogue between repetition and transformation, between the fixed and the fluid. Each variation unfolds like a facet of thought—playful, tragic, ironic, tender—until the material itself begins to dissolve, reconfigure, transcend. The work culminates in a Fuga, not as an academic finale, but as a culmination of voices—inner and outer, past and future. It grows from a single line into a cathedral of sound, strict and fervent, rational and ecstatic.

This is not simply a tribute to form, but to what form contains: lineage, intention, soul. Beneath every note lies Chuliá’s teaching—not just what to write, but why to write. This piece is a conversation across time. A ritual. A thank you. A return.

21 Tientos para piano solo

piano solo

I chose the word tiento deliberately. Not prelude, not étude, not impromptu. Tiento, a word with roots deep in the Iberian soil, evoking touch, intuition, the act of feeling one's way forward. It speaks to the body, to the hands, to the mystery of sound summoned through contact. It carries the ghosts of Spanish organists and vihuelists who improvised in cathedrals and palaces, tracing sacred geometries with their fingers.

These 21 pieces are my way of listening inward, and outward, toward memory, toward silence, toward the present moment. Each one inhabits a different mode, though I'm less interested in completeness than in resonance. Some of the tientos came to me like whispers in the dark, others like violent visions. They are not preludes to anything else; they are the thing itself. A diary of attempts, each one self-contained and open-ended.

I did not set out with a plan. The pieces grew in different seasons of my life, shaped by solitude, improvisation, and the search for a language that could hold contradiction: the archaic and the new, the written and the improvised, the precise and the uncertain. Some tientos are dense and formal, others barely breathe. A few dance. Some grieve. Others vanish before they can be named.

I do not pretend to explain them. They are thresholds more than declarations; places where something begins, or ends, or simply hovers. To tentar, in Spanish, is to try, to reach, to touch. In these 21 tientos, I try to touch something beyond the surface of the keys.

Piano Sonata

piano solo

This sonata is my love letter to the piano—my confession, my rebellion, my surrender. I composed it in a single movement, not to simplify form, but to allow it to breathe as a single breath, a long gesture, a river of transformations. Like Liszt’s great Sonata, or Berg’s haunting spiral of sonority, or Schubert’s Wanderer with its manic modulations and ghostly returns, I wanted to write something that unfolds organically, almost as if dreamed—without interruption, without chapters, without needing to explain itself.

It’s not a sonata about the piano. It is the piano—or rather, my lived experience of it. Its vastness. Its contradictions. Its silence and its thunder. In this sonata, I tried to touch the extremes of what the instrument can hold: fragility and violence, form and flux, clarity and chaos. I imagined the piano not as a tool, but as a living partner. As echo chamber. As cathedral. As animal.

The structure is elastic—there are thematic seeds that mutate, dissolve, reappear in disguise. Sometimes the music seems to remember itself; other times it forgets and starts anew. There are fugitive dances, moments of near stasis, eruptions of raw force. I wanted to inhabit time freely, with rigor but without rigidity. The sonata doesn’t follow a map; it follows gravity, memory, and instinct.

This piece is not meant to prove anything. It is not virtuosic for its own sake, though it does require surrender. It is a portrait of my hands on the instrument that shaped my life. A single movement—unfolding, breaking, healing—as if the piano itself were dreaming.

Fantasía para piano solo

piano solo

This Fantasy is a declaration of love—to Schumann, yes, but also to everything in me that resonates with his restless spirit. I didn’t set out to imitate him. That would be impossible—and beside the point. Instead, I tried to write a piece that lives in the same emotional weather, the same oscillations of tenderness and delirium, of intimacy and epic sweep.

What drew me to Schumann, always, is how music for him was never just form—it was thought, dream, hallucination, confession. He heard voices in his music. So do I. This Fantasy is full of them: fragments, characters, fleeting motifs that return like memories half-recalled. Some sections drift like letters never sent. Others erupt like diary pages torn in urgency.

There’s no fixed structure here. The music is led by impulse and transformation, as in his Fantasie in C, where time bends and narrative slips into reverie. There are coded messages too, buried in chords, intervals, rhythms. They may not be perceptible, but they are there—for me, and for anyone who listens with the inner ear.

Writing this piece felt like speaking to Schumann across time—sometimes as a friend, sometimes as a son, sometimes as a fellow castaway. His music has been my mirror in dark times, and my flame in bright ones. In this Fantasy, I tried to thank him—not with imitation, but with devotion.

It is music that longs, that questions, that remembers, that breaks, and then somehow sings again.

Toccata para piano solo

piano solo

This Toccata is a flash of energy—a sudden, breathless burst of rhythm and fire. It’s one of the shortest pieces I’ve written, but also one of the most demanding: a compressed whirlwind, meant to erupt rather than unfold. I wanted to write something that celebrates the sheer physical thrill of the piano—its percussive bite, its velocity, its capacity for controlled chaos.

The lineage, of course, is long: from the Baroque keyboard toccatas of Frescobaldi and Bach, to the 20th-century reinventions of Prokofiev, Khachaturian, and Ginastera. But I wasn’t trying to channel a particular style or composer. I was chasing a sensation—the sensation of fingers barely keeping up with thought, of musical ideas igniting and vanishing in a kind of ecstatic combustion.

There is no lyrical respite here—no consolation. The motoric rhythms grind, propel, tease; harmonies crackle and collide. Everything is on edge, slightly unstable. It’s music as adrenaline. As mischief. As dare.

I think of it as a musical spark: brief, bright, and burning fast. A kind of pianistic sprint—meant to leave both performer and listener just a little breathless.

Fantasia sobre temas de Ennio Morricone

piano solo

This piece is a thank-you—to cinema, to music, and to all the invisible threads that have consoled me through life. I composed this Fantasy as a pianistic homage to the great Ennio Morricone, whose melodies accompanied so many of my inner voyages, long before I knew how to name emotion, long before I could speak the language of harmony. His music seemed to float between worlds—between silence and song, memory and myth.

In transforming Morricone’s themes into a fantasy for solo piano, I wasn’t aiming to merely transcribe. I wanted to dream through them—to let them blur, shift, be refracted through my own voice and my own longing. This is not a suite, not a medley, not a set of variations. It is a reverie. A love letter in fragments. A nocturnal wandering across landscapes made of light, shadow, and sound.

Cinema has always been, for me, a second world—a refuge, a mirror, a secret chapel. Morricone’s music was often its soul. In writing this piece, I tried to make the piano sing like a film score does: with restraint, but also with grandeur; with tenderness, but also with inevitability. There are echoes of his iconic scores—yes—but also distortions, hesitations, moments where the themes dissolve into harmonic mist or erupt into improvisatory abandon.

The piano becomes, here, a kind of camera: panning across memories, zooming into a forgotten gesture, freezing on a note like a held breath. This Fantasy is my cinematic poem, an offering to the art that gave shape to my solitude, to my wonder, to my imagination.

In a world that often felt too loud, too fractured, cinema—and Morricone’s music—were my silences. My through-line. My consolation.

Eight Nocturne-Lullabies for Piano Solo

piano solo

These Eight Nocturne-Lullabies are whispered offerings—intimate, melancholic, and elemental. Rooted in the folk lullabies of Romania and Spain, they are not simply arrangements or evocations, but dream-objects: distilled atmospheres where memory, tenderness, and mystery interweave. Each piece is a veil between sleep and consciousness, a meditation on care, on exile, on time.

The nocturne and the lullaby—two forms traditionally associated with inwardness and quietude—are here fused into something deeper: not comfort, exactly, but a fragile kind of watchfulness. In these pieces, the piano does not dazzle—it listens. It rocks, it hums, it murmurs half-remembered melodies passed down through generations. Romanian modes bleed into Iberian rhythms; shadows of doina and nana, colinde and seguidilla, glide across the harmonies like distant lanterns swaying in the night.

Each lullaby is its own world: one full of gentle dissonances, cradled suspensions, rhythmic irregularities that echo the sway of a mother’s arms or the breathing of a child. And yet beneath the calm, there is always something trembling—a ghost of mourning, a question unasked, a note that lingers just too long. These are lullabies not just for children, but for exiles, for insomniacs, for the soul adrift.

In their quietest moments, these nocturnes touch the sacred: the ancestral, the maternal, the unspoken. They are fragments of a larger silence. Not so much music to lull someone to sleep, but music that remembers what it means to keep watch in the dark.

21 Danzas hispanas para piano

piano solo

These 21 Danzas hispanas are my personal homage to the vibrant, ancient, and ever-evolving world of Hispanic dance. I didn’t set out to write pastiches or direct folkloric imitations. What emerged instead were musical visions—echoes, fragments, reverberations of rhythms I’ve heard in plazas, in distant memories, in old recordings, or simply imagined.

Each dance is its own terrain: some are fiery, others introspective; some playful, others solemn. They are inhabited by the ghosts of jotas, zapateados, seguidillas, habaneras, fandangos—transfigured through the piano, filtered through my own sensibility, shaped by a lifelong fascination with rhythm, gesture, and melody.

I approached these dances not as a folklorist, but as a composer trying to listen inward, to what remains of a cultural memory when it becomes personal, intimate, and free. The result is a cycle that seeks not to reconstruct tradition, but to dream through it.

Sonata Bizantina

cello solo

The Byzantine Sonata for solo cello is a cosmic dramatic monologue—an invocation of ancient voices through the singular, resonant body of the cello. While it carries traces of the monumental sonatas of Kodály and Ligeti, and nods humbly to Debussy’s own poetic imagination for the instrument, this work is primarily an homage to the mystical sound world of Byzantine music. Named in quiet reverence to Paul Constantinescu’s Sonata Bizantină for solo violin, the piece draws from that same ancestral well of melismatic chant, heterophonic weavings, and the ever-present ison—the eternal drone that anchors and suspends, like a shadow of divinity humming beneath all expression.

Structured in a single movement that spirals and unfolds like a liturgy of the self, the sonata traverses terrains both earthly and celestial. Dance rhythms pulse through its veins, evoking folk rituals and festive ecstasies, while long, soaring lines echo the solemnity of sacred chant. A fugue emerges mid-course—structured yet volatile—a symbol of inner multiplicity, of thought splitting into voices. Virtuosic passages test the cello’s limits, not as a show of prowess, but as a reaching beyond: a grappling toward the ineffable. In its essence, Byzantine Sonata aspires to reconcile paradox—body and spirit, intellect and intuition, time and timelessness—in a single, unbroken breath.

Nocturno elegíaco

piano solo

Composed in memory of my dear friend Corneliu Rǎdulescu (1942 - 2019), a Romanian pianist of spiritual nobility and profound humanity, this Elegiac Nocturne is an intimate lament; sonic meditation on loss, remembrance, and the soul's enduring presence in music. Premiered live at the Enescu Hall of the National University of Music in Bucharest on November 26, 2019, the day he would have turned another year older, the piece seeks, beyond the notes, to invoke his silent and eternal presence.

Orchestral

Concierto para violin y orquesta "Il Filo"

solo violin and symphony orchestra

Il Filo—The Thread—is not merely a subtitle, but the soul of this violin concerto: a single, fragile line that weaves through chaos, through silence, through time. The thread is melody, yes—but it is also memory, longing, ancestry. It is what binds the self to the world, the past to the now, the visible to the invisible. In this concerto, the violin is that thread: a voice forever unspooling, forever searching, binding what would otherwise fall apart.

The music emerges from silence like a hand reaching into darkness—hesitant, tender, determined. The violin begins alone, spinning its line like Ariadne guiding us through the labyrinth of form and feeling. Around it, the orchestra does not merely accompany but surrounds, questions, resists, remembers. The structure is fluid, yet taut—rhapsodic and architectural. Moments of lyric repose give way to storms, cadenzas erupt not as displays of virtuosity but as soliloquies, moments of reckoning.

There are echoes of lament, of folk voices, of ancient dances half-remembered—threads of musical DNA drawn from across borders and centuries. And yet, nothing is quoted; all is transformed. The violin leads, not as hero, but as pilgrim. Its thread does not aim to conquer, but to connect—to find, within the fragmentation of modern life, a path back to wholeness.

Il Filo is a concerto not of spectacle, but of revelation. It asks: what do we hold onto when everything unravels? What remains, when only the line is left? In its most ecstatic and most intimate moments, the thread sings—not of resolution, but of endurance. The violin does not arrive. It continues. It remembers. It pulls us forward.

"Don Ruy, dis Mos", poema sinfónico

symphony orchestra

"Don Ruy, dis Mos" began as a joke, a pun, a provocation, a mirror held up to a certain corner of contemporary music that I find both fascinating and bewildering. The title is, of course, a word play on "ruidismo"; the cult of noise. But Don Ruy also evokes a character, almost a Don Quixote of sound: a knight errant tilting at the sacred cows of spectralism, ruidismo (bruitisme), and the asemantic abstraction that has come to dominate some academic and institutional musical circles.

This piece is a subtle mockery; but not a parody. I didn’t want to reduce or ridicule. I wanted to inhabit the language of those schools and tilt it, just slightly, until its contradictions began to hum. I borrowed their timbres, their orchestrational fetishes, their fragmentary syntax, but pushed them toward something more theatrical, even comical. There are sudden bursts of over-seriousness, gratuitous glissandi, harmonics that overstay their welcome, and silences that suggest profound meanings, but lead nowhere. I also reintroduce tone; not as nostalgia, but as subversion.

It’s a short piece, because satire rarely benefits from excess. Like a caricature drawn with care, Don Ruy dis Mos both respects and pokes fun at its subject. And though the piece critiques a kind of fetishization of sound over tone, it does so from within, not from outside. I know this music. I’ve studied it. I’ve admired much of it. But I also feel the need to question the sacredness it’s acquired, the dogmas it has spawned.

This piece is my way of asking: when did music stop meaning? When did sound become enough? And what might happen if we let tone, and not just timbre, sing again?

El Espectro, poema sinfónico

symphony orchestra

"El Espectro" is the spectral twin of "Don Ruy, dis Mos”, cut from the same ironic cloth, but bathed in a different kind of light (or shadow). Where "Don Ruy" charges forward with mock-heroic swagger, "El Espectro" lingers. It floats, hovers, and dissipates. A pun in title, yes, but also a meditation on the ghost of a school that once claimed to liberate sound from structure, and ended up binding it to yet another set of rituals.

Spectralism, in its original impulse, was revolutionary. It offered a way of listening; of composing with sound rather than onto it. I admire much of it, especially the rawness of early Grisey. But as time passed, I began to notice something spectral in another sense: the emptiness, the repetition of tropes, the endless stretching of form into ambient stasis, the cult of partials and the cathedral hush. It became, paradoxically, both anti-expressionist and hyper-aestheticized. Beautiful, yes. But also, dead.

So I wrote El Espectro as a kind of séance.

It begins in near silence; a slow accretion of inharmonicities, false spectral textures, and ambiguously intoned harmonies. The orchestra breathes in strange unisons, as if conjuring something that doesn't want to appear. The piece references spectral techniques, but with a twist: interpolated tones that ruin the overtone series, symmetrical spectra that cancel their own identity, and harmonic illusions that turn out to be tonal ghosts in disguise.

There's no climax, no clear direction; only a slow materialization and a slow vanishing. It is a piece that pretends to evolve, but only circles. It is sound becoming presence, then absence, then theater.

I imagine Grisey, half-smiling from the beyond, listening to El Espectro with both amusement and a raised eyebrow. Perhaps it is less a critique than a lament. A farewell to a ghost that still haunts our ears.

Tres Danzas Españolas para Orquesta sinfónica

These Tres Danzas Españolas are my orchestral tribute to the immense rhythmic and emotional vitality of Spanish dance traditions; filtered not through ethnographic fidelity, but through imagination, memory, and invention.

Each of the three dances draws inspiration from different regions and atmospheres of Spain, yet none of them is a direct quotation or reconstruction. Rather, they are dream-forms: shapes born from the echo of castanets, the tension of footwork, the melancholy of modal melodies, the ecstatic release of collective rhythm.

Composing for orchestra allowed me to explore the full coloristic and dramatic potential of these dances; to let the percussion section breathe like earth, the strings sing like voice, the winds whisper and call like distant bells or birds. These are not dances for the feet, but for the inner ear.

In writing them, I wanted to honor both the folk soul and the orchestral tradition; Falla, Turina, Albéniz, Granados, but also to find my own place within that lineage, however briefly, however humbly. The result is a triptych of imagined landscapes: familiar, strange, and full of life.

Danzas Latinas para orquesta sinfónica

symphony orchestra

These Danzas Latinas are a celebration of the shared rhythm that pulses through the Latin world; not in the narrow, contemporary sense of "Latino", but in the older, deeper meaning of "latinitas": the vast constellation of peoples and cultures shaped by the main Romance languages: Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, French, Romanian, and their diasporas across continents and oceans.

I conceived this piece not as a touristic patchwork, but as a poetic evocation of a common emotional grammar; a rhythm of the body and the soul that binds Naples to Lisbon, Veracruz to Marseille, Buenos Aires to Bucharest. There is dance in every Latin culture, but what fascinates me is the way each variation reveals something essential about gesture, identity, memory, and myth.

The music unfolds in a series of imagined dances; some fiery, others tender; some syncopated, others stately. These are not literal folkloric pieces, but original compositions rooted in the pulse of an ancestral Mediterranean imagination that has also crossed the Atlantic, adapted, morphed, survived.

If there is a through-line in this work, it is the body as bearer of memory, and rhythm as a way of knowing. These Danzas Latinas are my homage to that inheritance: not a museum of styles, but a living ritual of sound and movement that spans centuries and continents.

Totentanz

violin, piano, symphony orchestra, choir, percussion

Totentanz is a ritual of farewell—a requiem not of quiet resignation but of confrontation, defiance, and ecstatic grief. Scored for piano, violin, percussion, orchestra, and choir, the work was composed in the wake of my father’s death, when the very act of writing music felt like a struggle against oblivion. It is not a mournful procession but a dance with the abyss—a cry hurled into the void, charged with the paradoxes of love and rage, terror and transcendence.

In dialogue with the medieval Danse Macabre tradition and filtered through the modern intensity of works like Liszt’s own Totentanz, my composition invokes death not as a figure of finality, but as an unsettling companion: relentless, mocking, sublime. The piano and violin are like voices torn from the same soul—sometimes in communion, sometimes in conflict—surrounded by an orchestral force that surges and recoils like the breath of something unknowable. The percussion tolls and rattles like bone and bell, while the choir becomes a collective voice of the living and the dead—chanting, keening, whispering into eternity.

This Totentanz is a work of exorcism and offering, a farewell that refuses stillness. It is my father’s voice, my own voice, and the voice of all who have had to say goodbye and yet still live, still sing, still dance.

Concertino Breve para piano y orquesta de cuerdas

piano soloist and string orchestra

Premiered in September 2023 in KlaipÄ—da, Lithuania, with the KlaipÄ—da Chamber Orchestra under the direction of Alexis Soriano-MonÅ¡taviÄius, Concertino Breve is a two-movement work composed and performed by Josu De Solaun as soloist. Dedicated to the KlaipÄ—da Chamber Orchestra, the piece explores the liminal, hypnagogic space between wakefulness and sleep. The first movement, El Sueño (The Dream), emerges as an onÃrico, notturno, and misterioso meditation—a sonic drifting through shadowy inner landscapes. The second movement, La Danza ”“ Homaggio a Schnittke, bursts forth with grotesco, delirante, and frenetico energy, evoking a surreal, almost nightmarish ballet of fractured rhythms and uncanny humor. The work, both intimate and theatrical, stands as a hallucinatory diptych shaped by the volatility of the subconscious.

La Leyenda de Pigmalión

symphony orchestra

La Leyenda de Pygmalión is a symphonic poem in the grand tradition of Liszt and Strauss—where the orchestra becomes not merely a vehicle for sound, but a dramatic force, a psychological landscape, a mythic breath. Inspired by the ancient legend of the sculptor who falls in love with his own creation, the piece is less a literal retelling than a metaphysical reimagining: an inner odyssey of the artist haunted by the tension between ideal and reality, creation and solitude, flesh and illusion.

The music traces an arc of obsession and revelation, beginning in hushed ambiguity—as if chiseling through silence—before unfurling into surges of ecstasy, tenderness, and frenzy. Motifs emerge like shadows of a form not yet fully born, recurring and transforming as the sculptor’s inner world begins to collapse into the very image he has fashioned. Melodic fragments—at times lyrical, at times grotesque—mingle with dense orchestral textures and violent ruptures, evoking the blurred boundary between creator and creation, eros and transcendence, dream and delirium.

At its heart, La Leyenda de Pygmalión is a meditation on the sacred danger of art: its power to both elevate and consume, to summon the divine through human hands, only to confront us with our own exquisite ruin.

Concierto-Fantasía para piano y orquesta "Ianus Quirinus"

piano soloist and symphony orchestra

Ianus Quirinus is a Concierto-Fantasía in six movements—a visionary, protean work that seeks to inhabit and transcend the traditional concerto form. Conceived between 2020 and 2024, in years marked by rupture and reflection, the piece is named after the Roman god Janus—guardian of thresholds, of beginnings and ends, of war and peace—and his syncretic alter ego, Quirinus, protector of the civic soul. The work is an ode to duality, multiplicity, and metamorphosis.

The first movement, Allegro: Himno, opens with grandeur and invocation—an anthem not to victory, but to transformation. What follows is a wild Scherzo giocoso: Jácara y Tonadilla, a kaleidoscopic tribute to Iberian theatrical music, full of rhythmic wit, sly allusions, and virtuosic flair. Then, the first Intermedio—"El Espectro" (peán)—emerges like a hallucination, a spectral chant that hovers between memory and myth, shadow and light.

At the heart of the work lies the Adagio sostenuto: Endecha (treno), a funeral lament carved in marble—a stillness that aches, a slow dirge that sings of loss in timeless contours. The second Intermedio—Tiento de Falsas—is an introspective homage to the Spanish keyboard tradition, full of harmonic enigmas and whispered dissonances. The work concludes with Finale: Ditirambo, a Dionysian explosion of rhythm and color, where piano and orchestra surge toward ecstatic release, dissolving the boundaries between soloist and ensemble, form and frenzy, ritual and rapture.

In Ianus Quirinus, the piano is a trickster-priest, a poet-oracle, a battleground and a sanctuary. The concerto is not just a genre—it is a threshold. This work is a crossing.

Vocal

Requiem hispano

choir, symphony orchestra, vocal soloists

My "Requiem Hispano" is not a liturgical setting in the traditional sense; it is, rather, a meditation on loss, transcendence, and memory, filtered through the sounds and spirit of the Iberian Renaissance, and quietly haunted by my lifelong love for Brahm's "Ein deutsches Requiem". Like Brahms, I sought to write not a Mass for the dead, but a human Requiem: a music for the living who remain, who remember, who grieve, and who seek meaning through song.

In this work, I pay homage to the profound serenity and spiritual architecture of the great Spanish polyphonists: Morales, Guerrero, Cabanilles, Victoria, not through imitation, but through resonance. Their luminous counterpoint, modal clarity, and sacred restraint are all present here as distant stars guiding the texture of my own language. At times, fragments of that ancient spirit emerge in pure form; at others, they dissolve into orchestral and harmonic gestures that speak from today.

The Latin texts are chosen not only for their liturgical significance but for their emotional and philosophical weight. I wanted the music to breathe with both grandeur and intimacy, with solemnity and consolation. This Requiem is not about finality—it is about the trembling presence of what remains after loss, and the fragile hope that beauty might still lift us, even in mourning.

It is a personal work, deeply rooted in my cultural memory as a Spaniard, but reaching toward something universal. A requiem not only for the dead, but for all that is vanishing, and must be remembered.

Pribegiri: Cinco Poemas de Maria Pop

soprano and piano

This cycle of five songs, Cinco Poemas de Maria Pop, is both a love letter and a ritual; an offering shaped by years of living at the piano bench, breathing beside voices. My decades in New York as a pianist for singers, immersed in the worlds of opera, lied, chanson, canción, copla, and mélodie, have infused this work with a sense of intimate theatricality, lyric urgency, and emotional precision. Yet these songs are more than a reflection of that experience: they are born from the luminous, raw, and metaphysical poetry of my beloved wife, Maria Floarea Pop.

Each poem is a fragment of lived intensity, charged with a vulnerability that resists easy comfort, ranging from the apocalyptic longing of "Agonii", to the existential absurdity and ecological lament of "Pribegiri Superflue", to the expansive introspection of "Când timpul îţi pare prea larg". In "Pocăinţă", penance is no longer a gesture of guilt but of embodied mysticism, while "Febră" spirals into a fever dream of tactile memory, elemental and hallucinatory.

Musically, the voice is treated as a seer, a medium between speech and song, between confession and invocation. The piano, not merely an accompanist, becomes a shadow and a storm, a scaffolding of breath, echo, and rupture. These songs resist the ornamental; they strive instead toward the essential: to fuse poetry and music into something that aches, dreams, and burns.

Stabat Mater

choir, symphony orchestra, vocal soloists

Dedicated to the memory of my dear mother, my "Stabat Mater" is a work born not only of sound, but of silence; of the kind of silence that follows loss, and from which something sacred begins to stir. Deeply inspired by Szymanowski's haunting setting, which has long accompanied and unsettled me, this piece stands as a personal meditation on suffering, motherhood, and the strange intertwining of pain and the sublime. Composed in the same six-movement structure as Szymanowski's, it pays homage not only to him, but to a long lineage of composers who have approached this ancient text with trembling hands and open hearts: Arriaga, Haydn, Schubert, Dvořák, Gounod, Pergolesi, Poulenc.

Yet this Stabat Mater is also a reckoning. After years of spiritual distance, the death of my own mother in 2021 shattered a silence in me and reopened the path toward the divine; not in dogma, but in vulnerability. The music does not seek to comfort or resolve; it lingers in dissonance, in breath, in cries both human and more-than-human. It asks what remains when language fails, when grief outpaces reason; when a mother stands beneath the cross of her child, and when a child must carry the weight of a mother's absence.

This is not a liturgical work, but a spiritual one; raw, intimate, broken open by love and longing. It is a prayer I did not know I was still capable of saying.